New Zealand's Gas Decline: A Rapid Transition Opportunity

Brett Rogers, Director - Development

September 19, 2025

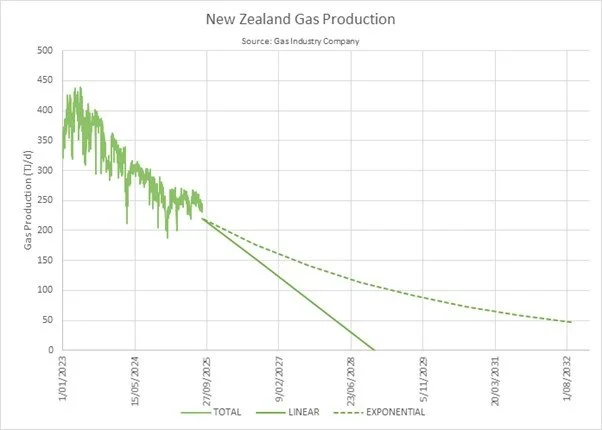

I recently created a graph of New Zealand’s gas production over the past two and a half years and forecast what might happen next. With 25 years in petroleum engineering, I was surprised to see that the decline fit a straight line just as well as an exponential curve.

Why is this surprising? While gas reservoirs typically decline exponentially due to pressure depletion, New Zealand’s water drive reservoirs behave differently — their performance hinges on unpredictable water breakthrough. What I hadn’t done before was forecast all fields together. The result: a straight-line decline that suggests our gas production will deplete faster than expected.

This helps explain why we’ve repeatedly been caught off guard by reserves writedowns. The Maui field was written down in 2002 for this very reason. We assumed poorer quality reservoirs like Kapuni, Pohokura, Mangahewa, and Turangi were less prone to water breakthrough — my analysis suggests otherwise.

The bad news: we may run out of gas much faster than anticipated. With prices now at $27/GJ, we must pivot quickly. The good news: this isn’t a crisis — it’s a chance to accelerate our energy transition.

We’ve been here before. After the Maui writedown:

Inefficient stations like New Plymouth were shut, and gas was redirected to Stratford and Huntly.

Rising prices made geothermal viable, leading to 1,000 MW of new generation.

Investment surged in new fields like Pohokura, Kupe, Turangi, and Mangahewa.

Cogeneration became attractive for industrial heat users.

Energy use became much more efficient, keeping costs down.

However, Methanex had to shut in for three years while new supplies were developed.

So what now? Methanex and other contracted gas holders could release supply to the wider economy — likely at a profit. Gas prices now align more closely with the long-run costs of renewables like wind and solar. Heat pumps can reduce industrial energy use, biomass becomes viable for modified boilers, and electric boilers and furnaces offer solutions for high-temperature needs.

The scale of the shortfall is significant. In the past 2.5 years, we’ve lost energy equivalent to 2.8 million households. If the trend continues, we’ll lose another 2.8 million in the next 2.5 years — a five-year loss equal to 40% of our electricity system. [In 2024, NZ used the equivalent of 31 million households of energy].

No one likes expensive energy, but no energy is worse. We are now able to develop new energy resources at globally competitive prices in a rapid transition. Here’s what will likely happen:

Gas producers should invest in infill drilling — even modest recovery is now economic.

Homes and businesses should electrify with efficient appliances and adopt solar.

Large industrial users must implement EECA transition plans.

Geothermal investment should be accelerated — doubling output by 2040 is achievable.

Electricity networks must support electrification, using new Commerce Commission funding pathways.

Generators need to fast-track wind, solar, and battery projects with global partners.

Banks can expand sustainability financing to support the transition.

Kiwisaver funds should invest in upstream and downstream energy infrastructure.

Government must continue attracting international energy investors.

E-fuel companies will play a key role in hard-to-abate sectors.

Landowners can benefit from hosting energy infrastructure.

Iwi will gain from deeper energy sector involvement.

Regional economies will thrive from new energy developments.

This transition is no longer a distant horizon — it’s a present-day imperative. With the key players acting together, New Zealand can lead the way in energy pricing, resilience and innovation.